How People Code Their Reality: Sensory Language and Representational Systems

How People Code Their Reality: Sensory Language and Representational Systems

The limits of my language are the limits of my world. – Ludwig Wittgenstein

What if the way a client speaks reveals exactly how they think, feel, and store experiences—and what if you could use that insight to enter their world more deeply, then guide them toward change?

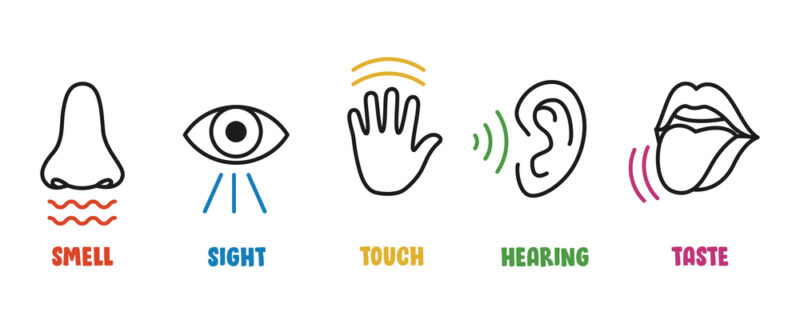

NLP teaches us that every thought, memory, and behavior is encoded in the brain using a blend of sensory channels: visual, auditory, kinesthetic, olfactory, and gustatory.[1]

Most people favor one or two of these systems, especially when under stress. By recognizing and matching a client’s dominant representational system, clinicians can more precisely attune to the client’s inner world—and open new pathways for insight and healing.

Understanding Representational Systems

In NLP[2], the five primary sensory modalities are known as VAKOG[3]:

- Visual (V): Pictures, colors, spatial layout (“I see what you mean”)

- Auditory (A): Sounds, tone, rhythm, words (“That sounds right”)

- Kinesthetic (K): Sensations, touch, emotions, movement (“It doesn’t feel right”)

- Olfactory (O): Smell (“It stinks”)

- Gustatory (G): Taste (“That leaves a bad taste in my mouth”)

Visual, auditory, and kinesthetic systems are the most commonly used in therapy. A client’s dominant modality often shows up in their language, posture, and even eye movements.

Why does this matter clinically? Because aligning with a client’s sensory coding system enhances trust, comprehension, and rapport. It also enables clinicians to help clients recode their experiences—changing how a memory feels, how a belief functions, or how a behavior is triggered.

A Sensory-Based Shift

Let’s look at an example:

A clinician is working with a trauma survivor who says, “It’s like I’m stuck in a dark tunnel, and I can’t breathe.” That’s a visual and kinesthetic representation. Instead of offering cognitive reframes like “Let’s think differently about this,” the clinician can respond in kind: “If you imagine a small light in that tunnel, where might it appear?” or “What would it feel like to move just an inch forward?”

This not only honors the client’s coding system—it gives them a felt sense of agency within it.

How to Detect a Client’s Dominant System

Pay attention to:

- Predicates (language): Visual = “see,” “look,” “clear”; Auditory = “hear,” “say,” “resonate”; Kinesthetic = “feel,” “grasp,” “get a handle on”

- Physiology: Visual processors often look upward; auditory processors glance side to side; kinesthetic thinkers look down or lean inward

- Pace and tone: Visual = fast and clipped; auditory = rhythmic; kinesthetic = slow and grounded

Once identified, clinicians can use matching predicates to speak the client’s internal language—enhancing resonance and therapeutic momentum.[4]

Clinician Reflection

This week, notice how you code your world. Do you tend to picture things, talk them through, or feel your way? Then, listen carefully to your clients. What cues are they offering about how they store and retrieve their experiences?

Try this simple experiment:

During your next session, pick one client and make a note of their three most frequently used sensory predicates. Then gently shift your own language to match that modality. Watch what happens to the rhythm, tone, and depth of the session.

[1] Kraft, William Alexander. The effects of primary representational system congruence on relaxation in a neuro-linguistic programming model. Texas A&M University, 1982.

[2] Heap, Michael. “Neuro-linguistic programming.” Hypnosis: Current clinical, experimental and forensic practices (1988): 268-280.

[3] Spînu, Stela. “NEURO-LINGUISTIC PROGRAMMING IN SUPPORT OF MEDICAL STUDENTS.” Values, education, responsibility. Pedagogical research. Editura Eikon 49-55.

[4] Kumari, J. Prabha, and S. Azmal Basha. “Neuro Linguistic Programming (NLP) for mind-body wellness.” IAHRW International Journal of Social Sciences Review 6.7 (2018): 1479-1483.