Skills for Working with Clients with Borderline Personality Disorder (Client’s perspective)

Skills for Working with Clients with Borderline Personality Disorder (Client’s perspective)

“This is the most difficult client I have ever had to treat. She calls me multiple times a day, at any time, expecting me to just pick up. I don’t know what to do anymore.” Leila was quite irritated, as she articulated these words to Rodis, the consultant to the HOPE Clinic.

“Leila, please tell me more about this client,” responded Rodis. “Well, I think she’s a borderline. She’s on lots of medications, and each time she comes here, she asks our psychiatrist to give her more. She’s driving everyone crazy. Her name is Emma,” retorted Leila. “Let us look into this case in more detail and talk about the skills required when working with patients and clients who are diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder,” replied Rodis.

Characterized by a long-term pattern of an unstable sense of self, unstable relationships with others, and profound difficulties with self-regulation, Borderline Personality Disorder is the most common of the ten personality disorders among those seeking treatment. A lifetime prevalence of 5.9% makes it more common than Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder, and, sadly, it has been highly stigmatized both by the non-clinician and us, the mental health professional and provider. Emma has been a challenge for the entire team, and Leila no longer knows what to do. Rodis offered his expertise, “Let us look into the skills required for working with patients and clients suffering from Borderline Personality Disorder. But, first, let us explore the reasons why it is crucial to possess these skills.”

Patient and Client perspective

Need to be understood

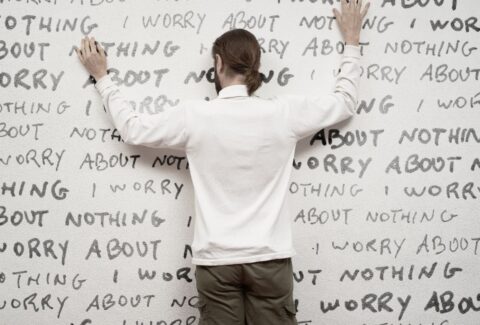

“Nobody ever understands me. My previous therapist, whom I trusted, ended up abandoning me. I have a lawsuit pending; how can you abandon your patient? I am a patient, and I am going to sue her for pain and suffering.” These were Emma’s words to Leila during her first visit. “Nobody ever understands me,” has been Emma’s truth and that of most patients and clients affected with Borderline Personality Disorder.

It is one of the reasons why they tend to seek treatment—the need to be understood-compared to those affected by Narcissistic Personality Disorder, a condition more common epidemiologically, but less so, in clinical setting. This “need to be understood” is also one of the elements required to establish and maintain a strong therapeutic alliance, to establish and maintain trust, and to establish and maintain safety. Allowing Emma to feel understood does not mean Leila has to agree to her statements. It simply means that Leila needs to validate Emma’s own truth, her own experiences, and that she has been living a life filled with pain and suffering.

“My previous therapist, whom I trusted, ended up abandoning me…” uttered Emma, and she later on followed with, “Everybody ends up leaving me.”

There is clearly a reason why everybody ends up leaving her. It means some form of relationship skills is needed in order for her to stop this cycle. However, she will need a safe place to use these skills; she will need to be understood, and this will only happen through new types of relationships, the types that will be able to model for her and also respond differently than her parents, friends, romantic relationships, and the way other therapists have previously reacted to her,” explained Rodis.

Victim and subject of biases

“Well, I think she’s a Borderline,” said Leila, responding to Rodis asking to know more about Emma. “She’s a borderline” has long been thought to mean, “she is just sick,” or “she is not really sick,” or “she’s just annoying,” or “she is a lost cause,” or “she just wants attention,” or “just pay no attention to her.” “She’s just a borderline” also has long been thought to mean that it cannot be helped or that nothing is really wrong. Whatever way it has been framed, we have unknowingly or unintentionally been using all these pejorative, stigmatizing, and discouraging epithets to further victimize and discriminate against our patients and clients suffering from this debilitating condition.

Until the DSM 5, the diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder had been placed under Axis II. This has erroneously helped spread the false assumption that this condition is less legitimate than disorders placed under Axis I, like Major Depressive Disorder, Schizophrenia, or Bipolar Disorder. For a condition that has a heritability rate of 40% and for which several brain abnormalities have been seen on imaging, it is time to stop further victimization, discrimination, and stigmatization against our patients and clients affected by Borderline Personality Disorder.

“This is the most difficult client I have ever had to treat. She calls me multiple times a day, at any time, expecting me to just pick up. I don’t know what to do anymore.” Leila was quite irritated as she articulated these words to Rodis, the consultant to the HOPE Clinic. “Let us look into this case in more detail and talk about the skills required when working with patients and clients diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder,” replied Rodis.

After conducting business as usual, it can be difficult to even imagine, much less to acknowledge, that we may have been doing things the wrong way all along. As a result, prior to even learning the skills required for working with patients and clients diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder, we first need to look at the reasons why these skills are required.

Our patients and clients need to be understood; they need to repair past relationships; and they have been the victim and subject of biases. These are the three main and crucial reasons why we all need the skills to properly care for them. These are also some of the reasons why we need to work to stop further victimization, discrimination, and stigma against this patient and client population and against all other individuals affected by mental illness. This endeavor starts with us.

References

-

Kernberg OF, Selzer M, Koenigsberg H, Carr A, Appelbaum A: Psychodynamic Psycho- therapy of Borderline Patients. New York, Basic Books, 1989.

-

Linehan MM, Heard HL, Armstrong HE: Naturalistic follow-up of a behavioral treatment for chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1993; 50:971–974; correction, 1994; 51:422.

-

Kjelsberg E, Eikeseth PH, Dahl AA: Suicide in borderline patients—predictive factors. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991; 84:283–287.

-

Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, Allmon D, Heard HL: Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:1060–1064.

-

Bateman A, Fonagy P: Treatment of borderline personality disorder with psychoanalytically oriented partial hospitalization: An 18-month follow-up. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:36–42.

-

Gabbard GO, Horwitz L, Allen JG, Frieswyk S, Newsom G, Colson DB, Coyne L: Transference interpretation in the psychotherapy of borderline patients: A high-risk, high-gain phenomenon. Harv Rev Psychiatry 1994; 2:59–69.

-

Gunderson JG: Borderline Personality Disorder: A Clinical Guide. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 2001.

-

Clarkin JF, Yeomans FE, Kernberg OF: Psychotherapy for Borderline Personality. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1999.

-

Adler G: Borderline Psychopathology and Its Treatment. New York, Jason Aronson, 1985.